Intent on the Air Force after high school, Fred Baker landed instead at Bemidji State University through the intervention of an official on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, who happened to be a BSU alum.

It was 1957, and Baker had just graduated as the only American Indian student at a Benedictine boarding school two hours from home, which he attended at the urging of a reservation priest.

“My folks were really adamant about me getting off the reservation,” Baker said of his early years on a ranch near New Town, N.D. “We lived in poverty, and the only way they saw out of poverty was to get an education and get out into the world.”

Grateful for forces that guided him to become the first in his extended family to attend college, the 78-year-old is eager to help others complete a degree at Bemidji State and take full advantage of all it has to offer, as he did.

Baker, who is three-quarters Mandan-Hidatsa Indian and one-quarter Irish, remembers his younger self as “a simple little Indian boy trying to make it in the white man’s world.”

Through his college experience and a lengthy career in American Indian health, education and development, he said, “I made it my world, and I had the right to do whatever.”

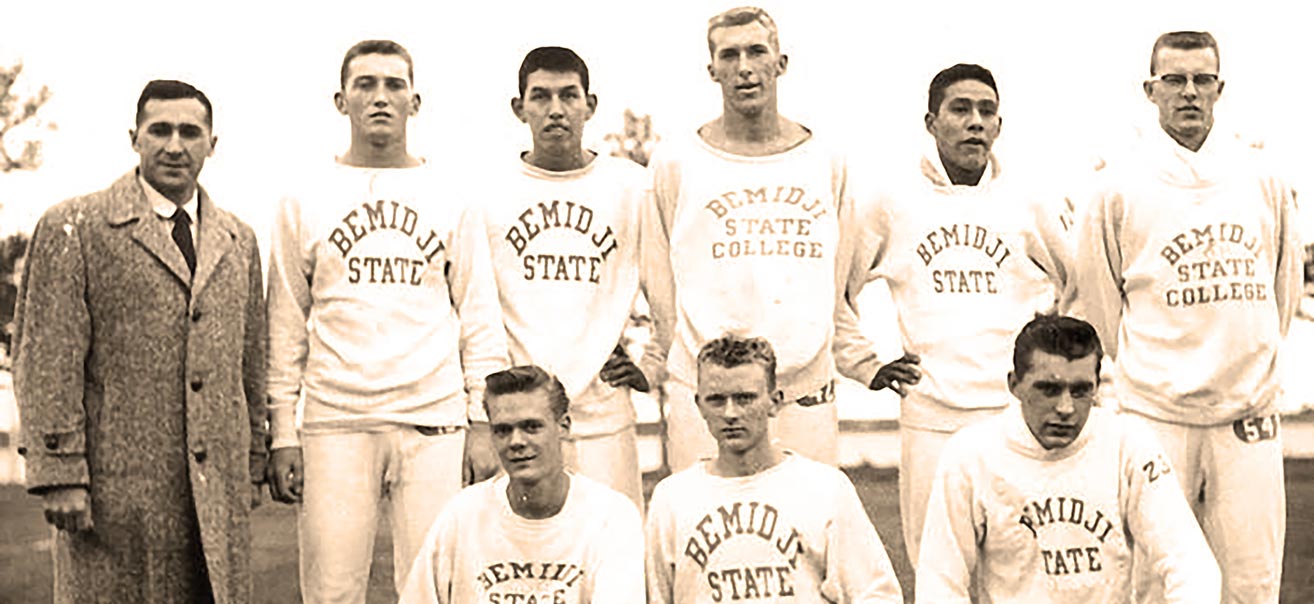

Baker wasted no time building a world at BSU, though he had never even heard of Bemidji until a month before he moved into Birch Hall. He ran cross country and track, joined the band and glee club and became assistant editor of the Northern Student newspaper.

He arrived in Bemidji with only enough money for one semester, thanks to a grant and loan from the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, so he quickly went to work at multiple jobs — in the kitchen at Birch, on the hall switchboard and as a night janitor in a savings and loan, among others.

“I kind of jumped in when I got to Bemidji,” said Baker, who was one of only a handful of native students. “I made up my mind, ‘When in Rome, do as the Romans do,’ so I got involved in all kinds of stuff. I didn’t sit back and wait for someone to invite me.”

He also got married, to a fellow student from Roseau, and two of their four children were born in Bemidji before he graduated with a degree in education.

Baker went to work as a teacher and coach in Naytahwaush on the White Earth Nation reservation before becoming a health educator with the U.S. Indian Health Service on reservations in North and South Dakota.

He briefly attended the University of Michigan on a public health fellowship and brought his young family to Los Angeles, where he helped implement what he now calls a “crazy” Bureau of Indian Affairs plan to move Indian households into metropolitan areas without employment or an adequate support system.

While doing post-graduate work as a Danforth Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, Baker seized an opportunity in 1969 to become a BIA employment assistance officer in Fairbanks, Alaska, where two years later he became the nation’s youngest BIA superintendent.

Then his father became severely ill, so he returned to North Dakota, taking a student services post at the University of Mary in Bismarck so he could keep the family ranch going. He was determined that his two younger brothers be able to stay in college.

“There were days when I had to leave work at 5 p.m., drive to the ranch to do chores half the night, and drive back to Bismarck be at work the next morning,” Baker said.

He continued his career in public health and health care administration, always with some direct or indirect connection to American Indian communities.

Even in retirement, Baker has stayed active in tribal leadership and advocacy, serving as chairman of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Elders Organization and as a member of the North Dakota Governor’s Committee on Aging, among other roles.

In 2002, he testified in Washington before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, helping win federal funding for a new Indian health center in New Town.

Baker, who learned the Hidatsa language as a child, has also lectured on the history and culture of what are known as the Three Affiliated Tribes, which helped the Lewis & Clark Expedition survive the winter of 1804-05.

Now divorced, he remains close to his daughter in Utah and two sons in British Columbia and Texas, as well as three grandchildren and members of his extended family. He lost his oldest son to a heart attack about five years ago.

Baker himself is a cancer survivor. In November 2015, surgeons at the University of Minnesota Medical Center removed his right kidney and an 11-pound malignant tumor.

In addition to family travel, Baker pursues his passion for high school and college track and field, attending major events such as the NCAA Track and Field Championship in Eugene, Ore., in early June.

His background as an athlete and an educator helped reconnect him to Bemidji State through Rob Bollinger, BSU’s former executive director of university advancement. Bollinger recalled his father’s career as a respected teacher and coach on the Standing Rock, S.D., reservation, and the two bonded as they discovered their overlapping backgrounds.

Last fall, Baker returned to BSU for Homecoming and served on a panel of American Indian alums at the American Indian Resource Center. He has since chosen to support scholarships for Indian students and make a financial commitment to BSU Athletics, as thanks for his years competing in green and white.

Baker sees the opportunities available at Bemidji State through the lens of his own experience, and he wants to open doors for other native students who need a boost, just like the one he got 60 years ago.

Baker sees the opportunities available at Bemidji State through the lens of his own experience, and he wants to open doors for other native students who need a boost, just like the one he got 60 years ago.

“BSU has a commitment to educating Indian students, and I support that very much,” he said. “There’s a need on the reservation for students with good academic training to come back and work. But I also think Indian students should not feel restricted to any particular thing. The world is open to them.

“They should look at the world and say, ‘I’m part of this world.’”