Each summer, Dr. Dale Greenwalt travels from his home in Maryland to northwest Montana, where he works to unearth long-lost life forms.

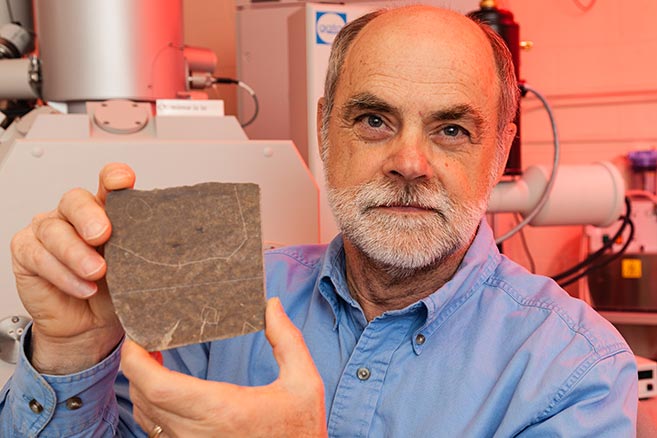

Greenwalt, a retired biochemist who earned his master’s degree from Bemidji State in 1976, garnered headlines three years ago when he and fellow researchers discovered the fossil of a 46-million-year-old blood-engorged mosquito near Glacier National Park.

The team has found numerous fossilized insects in the Kishenehn oil shale formation along the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, many of which are species never seen before. For example, a 46-million-year-old winged female ant was among 12 new species of prehistoric ants discovered within the shale, and a 46-million-year-old beetle was found to be the oldest yet to have zinc-lined mandibles.

“With all the papers we have published now, that number will soon be above 100 new species,” Greenwalt said. “We will be publishing extensively within the next year or so in a number of publications that demonstrate how exceedingly unique and valuable, in a scientific sense, these fossils are.”

His interest dates back to the mid-1970s when, after teaching math and science in Western Samoa through the Peace Corps, the Brainerd native decided to pursue a teaching certificate at Bemidji State University and figured he would get his master’s degree at the same time. Prior to joining the Peace Corps, he’d earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Minnesota.

“My interest in insects actually started at Bemidji State, where I took several courses in entomology from Dr. Harold Borchers,” Greenwalt said. “Dr. Borchers was a unique individual, and he helped me a lot. He was a huge influence in my life.”

Borchers, who retired in 1997 as a professor emeritus of biology and still lives in the Bemidji area, easily recalled his former student and said he not only was a dedicated worker but also had a “remarkable intellect.”

“Dale was a really good student, right up there at the top of the heap,” Borchers said. “There were other good (students) of course, but he was extraordinary.”

But Greenwalt’s interest in entomology did not become his career path, and neither did teaching.

After a year of teaching middle school science in Hendricks, he decided the profession was not for him and enrolled at Iowa State University, where he earned his doctorate in comparative biochemistry. He then completed a post-doctorate program at the University of Maryland and served as a professor of biochemistry at San Jose State University in California.

“The research I did was on, at that point and time, a membrane protein that was present in the cells that secrete milk,” he said. “Nothing was really known about it, so I characterized that protein, purified it, sequenced it.”

When his wife, Kim Warren, took a job with a pharmaceutical company in 1990, they moved to the outer Maryland suburbs of Washington. Greenwalt accepted a position with the research institute of the American Red Cross, where he continued his research into the membrane protein, finding it also was present in blood platelets.

When Kim later founded a biotechnology startup company called Poietic Technologies, Greenwalt served as its director of research. They both continued to work there, even after the company was sold.

When Kim later founded a biotechnology startup company called Poietic Technologies, Greenwalt served as its director of research. They both continued to work there, even after the company was sold.

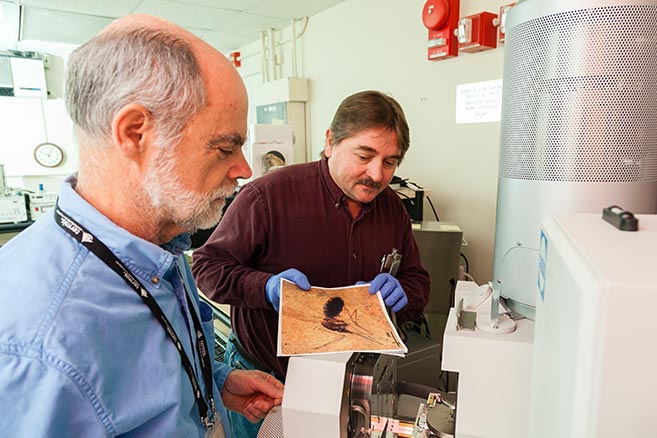

In 2007, Greenwalt retired from the biotechnology industry and realized he needed something to fill his time. He read online that the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History was looking for volunteers.

“Originally, the project they gave me was to put adhesive labels on 31,000 tiny white trays,” he recalled, noting that while volunteers complete essential projects, they aren’t always the most exciting.

“After a year, I was able to talk my way into an independent project, Because of my background as a scientist, I was able to initiate a completely new research program which involved my going out to Montana every summer to collect fossils.”

He had heard of a site near Glacier National Park where fossil insects had been discovered in the 1980s, but other than one paper published in 1989, no one had actively pursued it.

“It turns out it’s a place where some of the best fossil insects in the world are preserved,” Greenwalt said.

What is extraordinary about the fossils, he explained, is that not only are they structurally preserved, their original organic components are preserved as well. They’re also extremely small.

“There is strong bias toward tiny and fragile insects, like blood-engorged mosquitos, and really tiny insects, many of which are only a millimeter or even less (in size),” he said. “We found one beetle that was only three-fourths of a millimeter in length.”

Greenwalt said his team is now researching the shale formation itself, which dates to the Middle Eocene epoch, to determine what enabled such remarkable preservation. He believes it is the remains of a very shallow lake covered by a layer of green algae.

“The algae is very sticky and the insects would stick to it,” Greenwalt said. “The algae would grow up and over and encapsulate the insect, and in doing so would actually protect it from degradation and predation. Then, when the mat died, it would sink down to the bottom of the lake and it would contain that insect encapsulated in the algae, and it would become buried in more sediment and annual layers of those (algae) mats, and eventually become a fossil after millions of years.”

Greenwalt has now been retrieving and analyzing samples from the site for eight years, with no immediate plans to stop. While technically still a volunteer with the Smithsonian, he now has the title of research associate in paleobiology, which he said provides him with greater legitimacy when he reaches out to potential collaborators.

“I’m loving the work, and there is enough to keep me busy for a lifetime,” he said.

Written by Bethany Wesley