In the mid-2000s, Bemidji began to experience an increase in problems related to deer populations, including complaints from homeowners about property damage and accidents involving vehicle collisions with deer — some of which led to serious injuries.

“Essentially, the city’s deer population exceeded the cultural caring capacity,” said Dr. Brian Hiller, an associate professor of wildlife in Bemidji State University’s Department of Biology.

The city began exploring options to address its deer situation, which currently include a pair of special city archery hunts coinciding with the regular Minnesota archery season. Hunts are underway through Dec. 31 in the northeast section of the city and in a special limited hunt surrounding the airport.

To assess the current hunts and to properly consider any future expansion of the program, the city needed data. With support from Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the city was surveying its deer population every four years. Hiller thought more data would be beneficial, so he volunteered BSU students to help with the surveys.

“The city wanted to collect information to better understand the problem, and this was a perfect opportunity to give students hands-on experience doing real work in the field,” Hiller said.

With Hiller’s guidance, BSU students are currently conducting their fifth annual survey. He says the city is using the data collected during the surveys to look not only for areas where more attention might be needed to address its deer population, but also areas where current efforts — such as the archery hunt — are helping to keep it in check.

“The city is mainly interested in how many deer there are,” Hiller said. “They are looking for areas that have potential for increased complaints or for more deer-car collisions.”

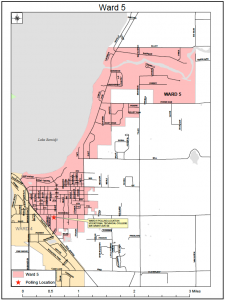

The surveys have typically focused on Bemidji’s Ward 5, located along the northeast border of Lake Bemidji — prime deer territory, according to Hiller.

“There are larger lot sizes with lots of scrubby, brushy edges,” he said. “If you were building deer habitat, it’d be perfect – you couldn’t design it any better. There’s a giant lakeside swamp and a forest that’s a state park, and then deer can literally go across the street and eat out of a bird feeder.”

Adam Maleski, a senior wildlife biology major from Little Falls, Minn., is in his second year participating in the surveys. He said the potential environmental impact of high deer populations has been easy to identify, particularly on the east side of Lake Bemidji.

“You can clearly see browse lines from deer at their very high densities,” he said. “It shows what deer are capable of – they can have a significant impact on vegetation, and they can significantly change a forest and plant diversity.”

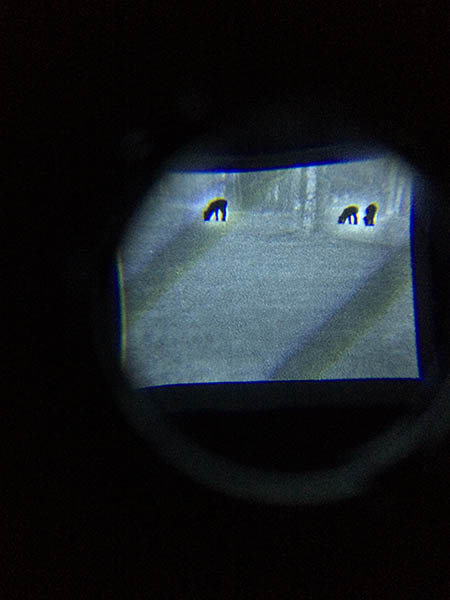

The process for gathering the data is simple — Hiller and his students take a university vehicle out after sunset and look for deer with spotlights and, after dark, thermal cameras.

“We start at sunset and we finish when we finish,” Hiller said. “When we see 20 deer, we can finish in two hours. Other times, it can take awhile.”

Students will announce when they spot a deer, and the team will gather information about the sighting – whether the deer is in someone’s yard, in the woods or in an open field; the distance and bearing from the vehicle when seen; and the number and types of animals spotted.

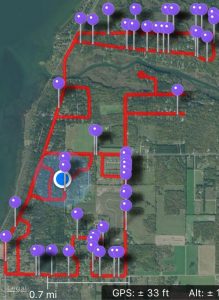

The team’s data is imported into Geographic Information Systems software, which is used to develop sighting maps for the surveyed neighborhood. The data can then be compared to previous surveys along the same route – and while the route is the same, the team uses different start and stop points along the way each time it visits a neighborhood.

“Deer are creatures of habit,” Hiller said. “If you keep the same route, you’ll see the same deer doing the same things.”

During an Oct. 25 survey, Hiller said his team spotted deer at 50 stops and recorded 65 animals – the most it had seen during a survey so far.

Maleski said the students have built competitions into the surveys to see who can spot the most deer during a tour.

“It’s a fun opportunity,” Maleski said. “You can make it into a competition of who sees more deer on their side of the vehicle. I saw 24 and you saw three, so I’m clearly better than you,” he laughed.

The increasing number of deer the group has seen, which Maleski describes as “definitely more” than the group observed during its 2015 surveys, helps reinforce the importance of the data Hiller and his students are providing – which also has led to Hiller’s inclusion on the city of Bemidji’s deer committee and requests for surveys in other parts of Bemidji.

“The city is getting more complaints from other wards,” Hiller said. “So instead of four surveys, this year we will do eight surveys and next year maybe 12.”

Maleski said the opportunity to participate in the surveys is invaluable and will benefit him as he looks toward his future and a prospective career with the DNR.

“Any time you can help with the DNR, especially as this is the field I want to go into, it feels good,” Maleski said. “I’m contributing something to their study or to their management that is going to be used in the future.”

Contact

- Dr. Brian Hiller, associate professor of biology, Bemidji State University; (218) 755-2212, bhiller@bemidjistate.edu

Links

- City of Bemidji: “Special Archery Deer Permits”

Bemidji State University, located in northern Minnesota’s lake district, occupies a wooded campus along the shore of Lake Bemidji. A member of the colleges and universities of Minnesota State, Bemidji State offers more than 80 undergraduate majors and 11 graduate degrees encompassing arts, sciences and select professional programs. Bemidji State has an enrollment of more than 5,100 students and a faculty and staff of more than 550. University signature themes include environmental stewardship, civic engagement and global and multi-cultural understanding.

Bemidji State University, located in northern Minnesota’s lake district, occupies a wooded campus along the shore of Lake Bemidji. A member of the colleges and universities of Minnesota State, Bemidji State offers more than 80 undergraduate majors and 11 graduate degrees encompassing arts, sciences and select professional programs. Bemidji State has an enrollment of more than 5,100 students and a faculty and staff of more than 550. University signature themes include environmental stewardship, civic engagement and global and multi-cultural understanding.

2017-B-S-001